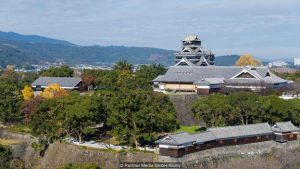

The Japanese castle that defied history

In a downtown park in the under-visited city of Kumamoto on Kyushu, the south-western-most of Japan’s main islands, a group of locals can be found painstakingly trying to complete what could be called the world’s hardest jigsaw puzzle. It’s a problem so huge the pieces cover the size of a football field. A riddle so challenging, it’ll take them the best part of 20 years to complete.

Together, they work with chalk-marked fingers, numbering hundreds of salvaged rocks arranged in checkerboard patterns, photographing each one, trying to determine the correct position of each piece. Often in sweltering heat, they scan row after row in almost revered silence, with heads bowed piously as if in prayer.

To the untrained eye, it appears a bamboozling exercise. But it is, in fact, a mission that’ll eventually see the blocks placed back into the fabric of the city’s most iconic structure: Kumamoto Castle, a fortification known throughout Japan because of its signature colour – black.

Finishing this process, returning the stones with prescriptive accuracy and repairing the wrap-around walls, commands respect. Because when the last remaining piece is completed, one of Japan’s most illustrious castles will have been brought back from the dead.

“It makes me so sad to see this,” said local guide Shoko Taniguchi, running her hand across the top of a block while showing me the reconstruction site. Ahead of her were weathered but wise-eyed workers, some wearing hard hats, others in surgical masks to prevent dust inhalation. All were stooped low, examining more than a dozen rows of stone blocks at least 50 deep. “This castle is more than a symbol for Kumamoto. It’s important to all of Japan. But today it’s a graveyard of desecrated headstones.”

What is it with Japan and its castles? Today, it’s almost impossible to visit the country without encountering at least one. Himeji’s dazzling white fortress Hakuro-jo, or ‘White Egret’ castle, has been rewarded by Unesco for its fortified network of more than 80 defensive towers. There is Matsumoto’s oily-black Karasu-jo, or ‘Crow’ castle, the country’s oldest surviving bastion dating to 1504. Tokyo, Osaka, Nagoya and the smaller cities of Odawara, Hikone, Takeda, Matsuyama, Kanazawa, Okayama and Gifu each have one. There are dry moats and dimly lit, dusty interiors. Ornate tiled roofs and faded reliefs of folk heroes. At times, it feels like there are so many that the design of one bleeds into the next.

But while castles are big news in Japan, they are especially so in Kumamoto. Following a magnitude 7.3 earthquake that hit the city on 16 April 2016, the city’s pin-up castle was brought to near ruin. Not only did the tremors destroy schools and offices, tragically killing 225 and injuring more than 3,000 others, but the aftershocks waylaid 190,000 houses, turning parts of the obsidian-black castle, a fortification that never succumbed to attack in more than 400 years of its history, into a confused mess.

Blocky turrets and curving stone walls, known as musha-gaeshi, collapsed. The grandest part – the tenshukaku, or castle keep – sustained seismic damage. And that was just for starters: roof tiles crumbled, foundations fell and the castle’s ornamental shachihoko (folkloric animals with the head of a tiger and body of a carp) dropped from the sky. Today, the fortification lies in disrepair, crowded to the margins with rubble, every chink in its armour revealed.

“I can’t imagine how complicated it must be to put it back together,” said Taniguchi, looking towards the five-storey tenshukaku tower, now hidden by a veil of scaffolding. “Maybe one day its magic will return.”

This sense of unwavering local pride, and Japan’s rigorous approach to safeguarding their heritage, has led to the mammoth reconstruction effort, one that’ll ultimately cost the Japanese government 63.4 billion yen. According to the current Kumamoto Castle General Repairs Plan, major works will start in 2018, with the castle grounds reopening bit by bit as completed areas are confirmed safe. Meanwhile, help continues to flood in from across Japan.

“The castle suffered a historic amount of damage in the earthquake, so the repairs need lots of time, money,

specialised knowledge, technology and manpower,” Issei Kanada, manager for the Protection of Cultural Property at the Kumamoto Castle Research Centre, told me. “Given its intrinsic cultural value, as well as its importance as a sightseeing destination, we plan to progress with repairs in the fastest, yet most efficient way possible.”

Despite the horrors of the earthquake, Kumamoto Castle has seen its fair share of drama over the centuries. The black bastion harkens back to the time of the samurai, an epoch when Japan was engulfed in a chaotic era of warring states and feudal dynasties. And the castle’s story is one that would almost be unbelievable in fiction.

Before it was built in 1607, Kyushu was teetering on pre-industrial revolution, with samurai lords jostling for power and influence in a series of land grabs. Change was coming to Japan. To the south in Satsuma (now modern-day Kagoshima), the death in 1598 of shogun Toyotomi Hideyoshi, a revered samurai and politician, led to rising tensions from rival factions, including the Shimazu clan, one of the most powerful families in Japan and a fierce opposition.

In order to protect Kumamoto in the event of an invasion, Kato Kiyomasa, who had served as Hideyoshi’s military commander, built the castle as a counter measure. Knowing the samurai’s death-or-glory maxim, Kiyomasa knew the castle had to be unassailable in the wake of an attack from his opponents. Deciding to build the ultimate defence, he erected a formidable citadel of 49 towers, 18 gatehouses and 29 gates. No-one would dare try and take it.

The castle’s pivotal moment came more than two centuries later, during the Satsuma Rebellion. This was the culmination of a long period of rebellions and reforms as Japan moved from feudal lords to the Meiji Restoration – and ultimately led to the end of the samurai.

In 1877, after hostilities between the Satsuma and Emperor Meiji in Tokyo had reached crisis point, samurai-commander-turned folk hero Saigo Takamori, who was from Satsuma, planned a march on Tokyo to cleanse the government of corruption. But given his route took him via Kumamoto, now under the control of the emperor and home to the Imperial Japanese Army’s largest garrison on Kyushu, he knew what had to happen. The castle had to fall.

The ruling Meiji government saw it coming, too. With 20,000 samurai flocking to the Satsuma banner, Kumamoto Castle would become a battlefield. If the garrison failed to hold the keep, the rebellion would spread like wildfire throughout Japan. Its loss, the emperor knew, had to be avoided at all costs.

“The castle’s garrison held off attackers for approximately two months – from 19 February to 12 April 1877 – without allowing a single person to enter,” Kanada told me. “The Satsuma Army was responsible for burning peoples’ homes and killing our ancestors in the fighting – and today people still have mixed feelings about this time. But what isn’t debated is the role the castle played: it proved its defensive capabilities in battle. And that’s very rare for a castle in Japan.”

Even that wasn’t the end to the drama. An accidental fire during the siege burned a section of the original keep down, the cause of the flames remaining unclear. One explanation, Kanada suggested, was that the garrisoned government army pre-emptively started a controlled burn to make the castle a harder target for cannons through the smoke. Another points at a traitor starting the fire.

As history now shows, what happened next helped define the Meiji Restoration, an episode that restored imperial rule to Japan exactly 150 years ago. The disheartened samurai fled back to Satsuma, before making their last stand at the Battle of Shiroyama in September 1877 (for a riff on that story, see Hollywood yarn, The Last Samurai, starring Tom Cruise and Ken Watanabe). Without Kumamoto Castle’s power to triumph, Kyushu – perhaps all of Japan – may look quite different today.

Which is why even a magnitude 7.3 earthquake couldn’t be the end for Kumamoto Castle. The true measure of a place isn’t what happens to it, but how it endures. And here is a castle that has defied history.

Before too long, it’ll be ready to be discovered anew.